| Genetics

January

2010, Response to this article in the Proceedings of the National

Academy

of Sciences

African Village Dogs, their

Relationships

to each other, Other Breeds, including Basenji, Pharaoh Hound,

Rhodesian

Ridgeback, Saluki and Afghan hound

Summary by Dr.

Dominique

de Caprona

© de Caprona

2009

No

Sloughi,

Azawakh,

Aidi

or AfriCanis in this study

All

photographs copyrighted to their photographers. Please do not use for any

purpose without asking.

Some of the dogs in

this

study, from North (Egypt) to South (Namibia). The muzzle is to control

the dog during blood sampling.

Egypt (Giza)

©

Carlos D. Bustamante Laboratory.

Egypt (Kharga)

© Carlos

D. Bustamante Laboratory.

Uganda Koome

island

~ Uganda mainland (Busoba) © Carlos D. Bustamante Laboratory.

North Namibia

(Okanbjengedhi)

~ North Namibia (Onhuno) ~ North Namibia (Oshikango) ©

Carlos

D. Bustamante Laboratory.

North Namibia (Cham

Cham)

© Carlos D. Bustamante Laboratory.

Central Namibia

(Tsumeb)

~ Central Namibia (Otavi) ~ Central Namibia (Grootfontaine)

©

Carlos D. Bustamante Laboratory.

The study

entitled "Complex

population structure in African village dogs and its implications for

inferring

dog domestication history" by Adam R. Boyko et al. (2009) was

carried

out to ascertain the genetic diversity of African village dogs and

compare

it to the high sampling diversity of East Asian village dogs which is

used

to argue that domestication of the dog happened in East Asia.

318 of semi-feral

village

dogs from 7 regions in Egypt, Uganda, and Namibia, were sampled and

compared

with 126 breeds of western bred dogs including Basenji, Afghan hounds,

Salukis, Pharaoh hounds, Rhodesian Ridgebacks, Salukis, as well as with

Puerto Rican street dogs, and mixed-breed dogs from the United States

of

America.

Egypt: dogs

were sampled in three distinct locales:Giza (animal shelter), Luxor

(animal

shelter and surroundings), and Kharga (rural desert oasis). The

geographic

distance between Giza and Luxor is greater than that between Kharga and

Luxor, but the desert could be a strong barrier to gene flow between

Kharga

and Luxor resulting in their populations being more genetically

distinct.

Uganda: 100

dogs

were

sampled

from a cluster of villages east of Kampala and 30 dogs

from three neighboring isleands of the KomeIsland group in Lake

Victoria.

Although the islands are close to each other and just 20 km off the

mainland,

the authors expected the lake might act as a genetic dispersal barrier.

Namibia:

Dogs from over a dozen villages and urban areas in the northern and

central

parts of the country were sampled. There are no natural barriers

between

sampling locations. However, a cordon fence exists which keeps

livestock

diseases from the North out of the southern part of the country. Dogs

are

not forbidden to go across the cordon and can get through the fence

themselves.

Dogs within 100 km of both sides of the cordon were sampled, as well as

from populations within 10–20 km of the fence, to see whether this

fence

had any isolating effect.

To determine the

degree of

non-native admixture in African dogs the following populations were

sampled

16 Dogs of two

shelters

in Puerto Rico,

102 known

mixed-breed dogs

from the United States of America

Samples from dogs

from previous

studies (Parker et al.) representing 126 breeds, including 129 dogs of

the following breeds (western bred): Afghan hounds, Basenjis, Pharaoh

hounds,

Rhodesian Ridgebacks, and Salukis were use for comparison.

Mitochondrial

DNA (mtDNA), microsatellites,

and SNP markers were used to characterize population structure

and

genetic diversity.

Mitochondrial

DNA:

680 bp of the mitochondrial D-loop were sequenced, including the 582-bp

region described previously by P.Savolainen et al. (2002)

Microsatellites: 227

village

dogs

were

typed on a 89-microsatellite panel.

SNP markers:

300

SNP markers were analysed from 168 village dogs, 102 mixed-breed dogs,

and 126 western bred breeds.

Microsatellites,

and

SNP

markers:

The authors found

that Puerto

Rican street dogs clustered with the mixed-breed dogs from the United

States,

indicating these dogs are all breed admixtures.

For the other

populations

five groupings were consistent for the African village dogs: the

Egyptian

dogs, the Ugandan mainland dogs, the Kome Island dogs, the Northern

Namibian

dogs, and admixed dogs in a few of the village dogs.

84% of African

village

dogs outside of central Namibia showed little or no evidence of

non-native

admixture, whereas all central Namibian dogs had more than 25%

admixture,

most with more than 60%.

Central Namibian

dogs show

virtually no genetic differentiation from American mixed breed dogs.

Egyptian dogs from

Giza

and Luxor show little differentiation also.

A clear

separation

was found between Egyptian and sub-Saharan populations and between

Ugandan

and Namibian populations.

Dogs from

Kharga were

the most distinct whereas dogs from mainland Uganda and northern

Namibia

(2,900 km apart) show only moderate differentiation.

Three breed

groups

were differentiated: Basenjis on their own, Salukis and Afghan hounds

clustering

close together*,Rhodesian

Ridgeback

clustering

with

the Pharaoh hound.

Mitochondrial

Diversity:

47 haplotypes were

found

in the African dogs, 9 haplotypes in the Puerto Rican dogs, two

of

which found also in the United States mixed breeds All haplotypes were

in the A (33 African haplotypes), B (6 African haplotypes), or C

(8African

haplotypes) clades, the 3 which are believed to contain 95% of domestic

dogs.

18 of the African

haplotypes

haf not been described by Savolainen et al.: 14 in A clade, 1 in B

clade,

and 3 in C clade. The Puerto Rican and United States mixed-breed dogs

had

8 A clade and one B clade haplotypes (1 haplotype, a Puerto Rican A

clade

haplotype, was not previously described)

Local mtDNA

diversity

did not differ systematically between African regions and similarly

sized

regions in East Asia, the purported origin of domestic dogs.

Conclusions

This study shows

that African

village dogs have complex population structure resulting from

geographic

distance, local gene flow barriers, and the presence or absence of

non-african

DNA in some populations. Most importantly the vast majority of the

African

village dogs could be classified as indigenous (less than 25% of

non-African

ancestry) and some as non-native (more than 60% of non-African

ancestry).

Only 7 % showed intermediate level of African ancestry.

The authors state:"The

lack

of

consistent

levels of admixture within regions suggests that

non-indigenous

dog genes are quickly removed from village dog populations, or that

admixture

with non-indigenous dogs is a very recent phenomenon in these areas."

The populations

with non-native

ancestry were from central Namibia, where every dog had significant

levels

of non-african admixture, and Giza, where all dogs showed some, usually

low, level of admixture. This background level of admixture in Giza is

thought by the authors to reflect the relative proximity of Giza to

Eurasia.

Groupings were detected among the admixed dogs which could result from

ancestral breeds being different in various individuals.

The African

village dogs

grouped in a large cluster separated from the Basenji, Saluki/Afghan

Hound,

Rhodesian Ridgeback/Pharaoh Hound clusters. The Egyptian village

dogs were somewhat closer to the Saluki/Afghan, the Ugandan and North

Namibian

dogs closer to the Basenji. The Rhodesian Ridgebacks and Pharaoh hounds**were

closer to mixed-bred dogs, suggesting these breeds have had admixture

of

non-African dogs.

Influence of

barriers

to gene flow:

The 230 km of desert

separating

the Kharga oasis from Luxor led to much stronger differentiation

between

the populations of village dogs in these areas, than the 500 km Nile

corridor

between Luxor and Giza.

The dogs from the

Kome islands

which lie 10–20 km from the mainland in Lake Victoria were much more

differentiated

from mainland dogs in Uganda than were northern Namibian populations

2,900

km away.

Heterozygosity was

high

across all genetic marker types in all village dog populations except

those

of the Kharga oasis and the Kome islands (populations which are more

isolated

and likely smaller, resulting in higher levels of inbreeding).

A surprising

result:

the samples taken at a 20–100 km distance between northern and central

Namibian populations on each side of that country’s Red Line veterinary

cordon fence showed a stark population boundary—dogs north of the

cordon

averaged 87% indigenous African ancestry while those south of the

cordon

were only 9%African. For the past 100 years, this fence under

police

watch has separated the indigenous human populations (to the north)

from

white settlers (to the south)***.

This

fence is now used to restrict livestock from crossing southward.

In their own

words, the authors

state: "African village dogs exhibited a similar level of mitochondrial

D-loop diversity to that of the dogs sampled by P. Savolainen at

al.(2002)

in East Asia, the putative site of dog domestication. Although we do

not

suggest that Africa is actually the site of dog domestication, we do

believe

that an East Asian origin of dogs should be further scrutinized,

especially

as Africa also has numerous private haplotypes and East Asia has no

private

haplogroups, with the possible exception of clade E"

Aknowledgements

I thank A.R.Boyko

for reviewing

this text and for granting permission to use the photos of African

village

dogs, as well as all the other photographers who provided pictures for

this page.

References

Adam R. Boyko,

Ryan H.

Boyko, Corin M. Boyko, Heidi G. Parker, Marta Castelhano, Liz Corey,

Jeremiah

D. Degenhardt, Adam Autona, Marius Hedimbi, Robert Kityo, Elaine A.

Ostrander,

Jeffrey Schoenebeck, Rory J. Todhunterd, Paul Jones, and Carlos D.

Bustamante

(2009):"Complex population structure in African village dogs and its

implications for inferring dog domestication history" in

Proceedings

of the National Academy of Sciences.

P. Savolainen,

Zhang Y,

Luo J, Lundeberg J, Leitner T (2002): "Genetic evidence for an

East

Asian origin of domestic dogs." Science 298:1610–1613.

Author's notes:

* Among the

countries of origin of the Saluki (Arabian peninsula, Syria, Iran,

Iraq)

Iran shares borders with the country of origin of the Afghan Hound

(Afghanistan).

**

The Pharaoh Hound is indigenous to the island of Malta in the

Mediterranean

sea, not far from other European breeds. The Rhodesian Ridgeback is

considered

to have been developed by crossing the indigenous Hottentot ridged dogs

with dogs imported by the Dutch, German and Huguenot settlers in the

16th

and 17th centuries (Danes, Mastiffs, Greyhounds, Salukis, Bloodhounds).

*** The

German settlers had imported European breeds.

Basenji and

Pharaoh

Hounds, both © Schwab

Afghan Hound ©

Liz

Gross von Hübbenet ~ Saluki ©

Nina

Neswadba

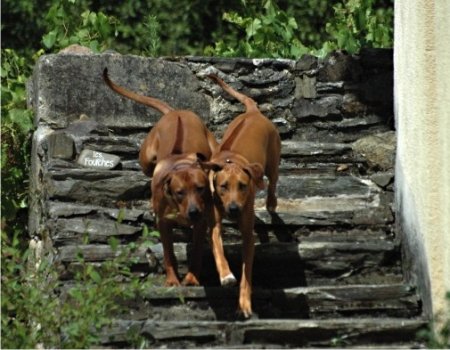

Rhodesian Ridgebacks

showing

their ridges © Bonnie van den Born ~ Rhodesian

Ridgeback

©

von

Elm-Weber

.

ABOUT

THE

AUTHOR |