| Genetics

Sloughi,

Saluki, Saluqi…

Genetic

Data Help Separate Semantics From Evidence

Dr.

Dominique Crapon de Caprona and Dr. Bernd Fritzsch

© Fritzsch/de

Caprona

2004

article

copyrighted with the Library of Congress 2004

do

not

use

any

parts,

sentences or pictures without written permission of

the authors.

Reproduced

with permission from Dogs in Review in which this article was first

published

(Hound Breeds Issue, July 2004)

“Oriental

Greyhounds: I. Slughi, Tazi or Gazelle hound, or Slughi Shami… II.

Ahk-Taz-eet

or Kirghiz Greyhound… III. The North African Slughi, or Slughi of

the Sahara... IV. The Barukhzy Hound, or Afghan Greyhound… V. The

Rampur

Hound, or Greyhound of Northern India… VI. The Poligar hound, or

Greyhound

of Southern India…

It

should be the object of all those who import the Greyhounds of the

East,

and breed them in this country, to try to keep distinct the different

varieties,

which in many cases have been so carefully preserved in their own

lands.

The historic interest attached to each breed is alone a sufficient

inducement

to do so.”

Amherst

F.(1907,

Oriental

Greyhounds

in

Cassell’s New Book of the dog, ed. R.Leighton

Ch.LVI, London)

Sloughi

Smooth

Saluki

~

Feathered

Saluki

Ever since sighthounds, greyhounds or Sloughis/Salukis were imported

from

their countries of origin in Asia and Africa into the western world,

numerous

myths about their origin have abounded. Clearly, except for the

Greyhound

and some smooth-coated dogs around the Mediterranean Sea, no other dog

of the 420 or so known breeds (of which the AKC recognizes less than

half)

resembles these hounds. Their swiftness and stamina, their elegant

build

and their noble attitude all contribute to the fascination these breeds

have generated among the dog fanciers in the western world.

History

shows

sighthound-like

dogs

depicted

in ancient images in the countries

of origin that resemble in many ways sighthounds still living there

today.

Consequently, some fanciers assume that indeed Salukis are ancient and

may have arisen some 2,000 or more years ago and may be the oldest

breed

of domesticated dogs. The images found in Egypt and Tepe Gawra suggest

that such smooth and coated sighthounds might be even older and date

back

to the earliest civilizations known to modern man.

Be

this

as

it

may, the checkered history of many countries in North Africa

and Southeast Asia raises certain doubts about the undisturbed

continuity

of the breeding of these hounds across such long expanses of time. In

addition,

the vast geographic area over which these sighthounds are spread,

combined

with limited accessibility in certain remote areas, raise issues of

geographic

isolation and limited genetic exchange which eventually could alter the

genetic composition of various local populations. Nevertheless, based

on

certain features, in many cases not shared with more distantly related

breeds, it seems reasonable to group all these hounds of the Orient and

North Africa into a single group with other comparatively built dogs:

the

lop-eared sighthounds of many national and international dog registries

of today (Afghan Hound, Azawakh, Saluki, Sloughi)

Among

the

various

sighthounds

found throughout Africa and the Middle East,

none has stirred more passion than the Sloughi/Saluki/Saluqi group of

hounds.

In part, the debate revolves around the name, which describes in Arabic

the local sighthound or windhound. Since in a given area only one of

those

hound types typically exists, there was no need to have more than the

generic

name that was equally used to describe the specific local variety. Of

course,

this linguistic confusion of generic and specific, combined with

various

transliterations of Arabic into European languages and the fact that

both

the colloquial “Sloughi” and the classical “Saluki” may be used to some

extent interchangeably, have confused this matter even more. This

confusion

is well summarized in Waters’ book on the Saluki ("The Saluki in

History,

Art and Sport," by Hope and David Waters, David & Charles, 1969),

and

the reader is referred to this book for more detail.

In

the

modern

era,

the

Sloughi of North Africa (henceforth simply referred

to here as Sloughi) was first imported from the French North African

colonies

to France in the 1800s. These dogs were well known in France since 1850

through the books of General Daumas and also featured at international

dog shows. Holland also was a major home of the Sloughi, brought back

at

the end of the 19th century from Africa by Auguste Le Gras.

Feathered

sighthounds were portrayed on the European continent earlier than 1700,

and were sporadically seen in the UK in the 18th century. It was around

the turn of the 20th century that serious breeding started, following

the

first imports of “Slughi Shami”to England by Lady Florence Amherst (as

she then named them) , and later on the feathered sighthounds of

Brigadier

Lance. These dogs provided the ancestors of the modern Saluki in the

West.

After

the

First

World

War ended and with the demise of the Ottoman Empire,

both the French and the British had access to the Middle East and

brought

back many Salukis (named thus in England since 1923). Surprisingly, it

appeared that the Saluki came in two varieties, a feathered variety and

a smooth variety. Logically, having a sighthound from the Middle

East that had features in common with the smooth Sloughi of North

Africa

and the smooth sighthound-like dogs painted on the murals of ancient

Egypt

raised a number of questions about the relatedness of these dogs.

Different

opinions

developed

about

this

subject over the past century and are summarized

as follows:

1)

Sloughis of North Africa and Salukis both belong to the group of

oriental

lop-eared sighthounds but are not more closely related to each other

than

the Saluki is with his eastern sighthound relatives, the Afghan Hound

or

the Tazi and Taigan of the steppe. The arguments in favor of this

scenario

assume the geographic isolation of the Sloughi in the vast expanse of

Northern

Africa and rely on the morphological differences, now also reflected to

some extent in written standards of the breeds. It assumes that the

Sloughi

and Saluki evolved in their respective countries of origin and should

be

kept distinct. We will refer to this idea as the “Sloughi hypothesis”

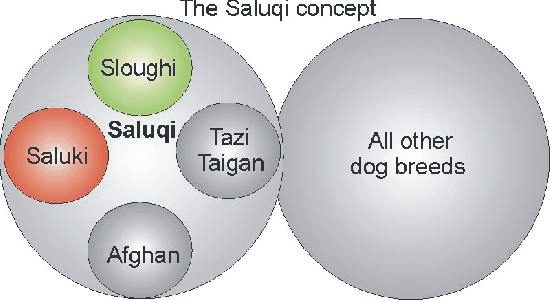

Fig.

1.

The

Sloughi

and

Saluki today form distinct breeds, with some potential

overlap of both breeds with each other and with other dog breeds.

2)

In contrast to this idea is the assumption that the different

geographic

varieties are tightly interconnected through interbreeding and all

Southwest

Asian and African sighthounds form a single large “breed”. The

underlying

assumption here is that western breeds known as Afghan, Saluki and

Sloughi

are artifacts of the small extracted gene pool used to found those

varieties

now registered as distinct breeds in the West, and do not reflect the

situation

in the countries of origin which show continuity in both phenotype and

the underlying genotype. We will refer to this hypothesis as the

“Saluqi

hypothesis.”

Fig.

2.

The

Sloughi/Saluki/Tazi/Afghan/Taigan

of

today are varieties of

one breed, the Saluqi, with little overlap with other dog breeds.

3)

A variation of this latter idea is the assumption that among Oriental

and

African hounds three varieties are particularly related to each other:

the smooth and feathered Salukis of the Middle East and the

smooth-coated

Sloughis and Azawakhs of Africa. This idea assumes that the African

Sloughi

and Azawakh were derived from the Saluki following the Arab invasion of

North Africa in the 7th century. We will refer to this hypothesis

as the “Saluki hypothesis.”

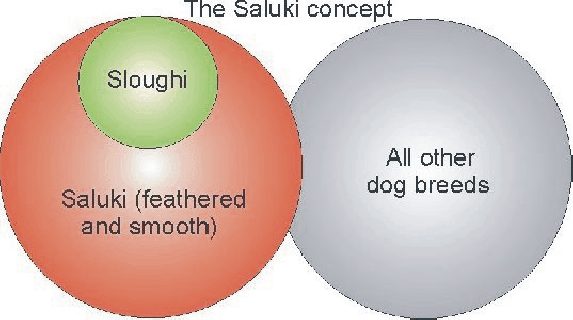

Fig.

3.

The

Sloughi

is

a variety of the Saluki with some potential overlap

with other breeds.

Numerous arguments have been raised over the years by proponents and

opponents

of each of these three hypotheses. With the recent completion of a

large

analysis of the mitochondrial DNA of 654 dogs of some 124 known breeds,

as well as other indigenous dog and wolf populations, the implications

of these opinions can for the first time be tested. The samples

processed

included 8 Sloughis, 15 Salukis, 6 Taigans, 1 Tazi, 10 Basenjis, and 5

Afghan Hounds.

The test consisted of sequencing an approximately 582-base-pair stretch

(* SEE FOOTNOTE) of mitochondrial DNA. This genetic material is only

inherited

through the female lines, as male sperms lose their mitochondria upon

entering

the female egg. In other words, such a study provides insights

exclusively

into the female background of a given population, no matter what the

male

looked like and what his genetic material was. Analyzing the male

genetic

background of a population requires sequencing of the male-specific

y-chromosome

that is only inherited from male to male without contribution from the

female. Such an analysis is on its way, but data are not yet available

(P. Savolainen, personal communication).

We

used the mitochondrial DNA data provided by Dr. Savolainen and looked

at

how they fit with the three ideas outlined above. We wanted to know:

1) Are

Sloughis and Salukis genetically distinct or not? Genetic

distinctness

would support the Sloughi hypothesis (Fig. 1), genetic similarity the

Saluqi

(Fig. 2) or Saluki hypothesis (Fig. 3).

2) Do

Sloughi and Saluki share genetic material with other breeds that

co-exist

in the same geographical area and potentially crossed with them in the

distant past? Are these two breeds embedded genetically into

their

geographical origin while maintaining their unique looks.

Logically,

the more genetic material is shared between these breeds and nearby

totally

different looking breeds, the less likely it is that consistent

selective

breeding took place over centuries.

3)

Are there distinct genes in Salukis and Sloughis not shared by other

breeds?

If the majority or all of the genetic sequences in a given breed are

unique,

it would indicate a long history of breeding from distinct females and

would support the hypothesis that Sloughis and Salukis are distinct

breeds.

The

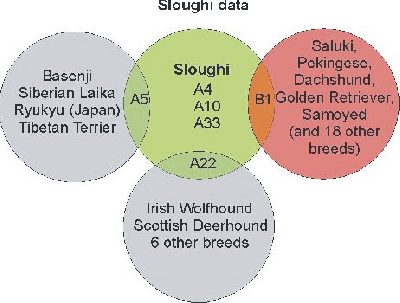

Sloughi:

The

six

sequences

found

in the eight Sloughis are 50% unique to the Sloughi

and not shared by any other breeds analyzed thus far (A4, A10, A33; 2

animals,

2 animals and 1 animal respectively). Of the three sequences

shared

with other breeds, one is shared with another African breed, the

Basenji

(A5, 1 animal) but also with three breeds from Japan, Tibet and

Siberia.

Another sequence is shared with eight other breeds (A22, 1

animal):

Boxer, English Setter, Irish Wolfhound, Nguni and Sica (Africa),

Scottish

Deerhound, Saint Bernhard, and Tibetan Terrier. The last sequence

(B1, 1 animal) belongs to a different sequence group and is the only

one

shared with the Saluki, but also with 23 other known breeds, as well as

a large group of dogs from China and Indonesia. Among the breeds

are the Dachshund, Doberman Pinscher, Finnish Spitz, Pekingese, Golden

Retriever, Samoyed and Shiba (Fig. 4). These sequences are

provided

by Sloughis that maternally originated, recently or in the past, in

North

Africa, and of which some represent several well established European

and

American lines.

Dr. Savolainen and colleagues calculated that a single base

substitution

*(foot note) reflects a mutation rate of about 26,000+-8,000

years.

The three unique sequences found in Sloughis are one or more

substitutions

removed from other breeds. This suggests that the descendants of these

three lines may have stayed in North Africa for several thousand

years.

This suggestion is supported by the sequences shared with the Basenji,

the Nguni and the Sica, African breeds that are now found only south of

the Saharan desert. At the same time the geographical range of

the

other breeds who share this sequence (A5) suggests that it might be

very

old and thus widespread across Eurasia and Africa. The two other shared

sequences suggest different things. The A 22 sequence could be

related

to the invasion of North Africa by Germanic tribes in 5th-6th century

or

could simply reflect the fairly widespread distribution across Europe,

Africa and Asia of this sequence and might not be related to any

specific

historic event. The B1 sequence shared with the Saluki does not

necessarily

reflect the invasion of North Africa by the Arabs and their hounds in

the

7th century, but could be related to events long lost in the past, as

it

is shared with other widely distributed breeds of dogs. Unfortunately

this

study cannot tell us the following: was the maternal line a Sloughi or

were the mitochondria contributed by the other breeds, perhaps now

extinct?

Nor can we know the timing of these events.

These

results

strongly

support

the idea of geographic isolation with some

incorporation of three widely dispersed female sequences for the

Sloughi.

The unique sequences strongly support the notion that the Sloughi is a

genetically unique population of sighthounds and the sequences shared

with

the Basenji, Sica and Nguni indicate that this breed is, on the

maternal

side, embedded in Africa, possibly for thousands of years.

The

Saluki:

The

eight

sequences

found

in the 16 Salukis are 25% unique to the Saluki

and not shared by other breeds analyzed thus far (A43, B15, 1 animal

each).

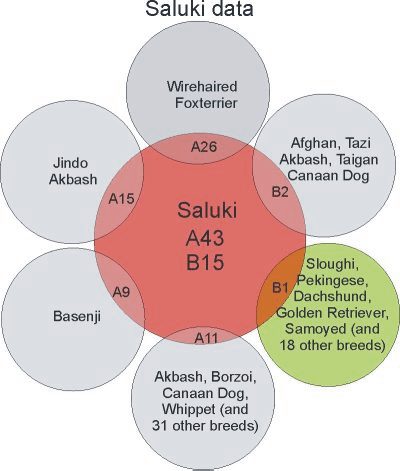

Six sequences are shared with other breeds (Fig. 5). For example, A9 (1

animal) is shared only with the Basenji, A26 (2 animals) only with the

Wirehaired Fox Terrier of Britain, and A15 (1 animal) is shared with

the

Korean Jindo and Akbash from Turkey. The three sequences shared

with

numerous other breeds constitute about 37.5 %. B2 (7 animals), is

shared with the Afghan, the Akbash, the Canaan Dog, the Taigan and the

Tazi from Kazakstan. B1 (2 animals) is the only one shared with the

Sloughi,

but it is also shared with 23 other known breeds as well as a large

number

of dogs from China and Indonesia. A11 (1 animal) is shared with over 35

breeds (Akbash, Akita, Basset Griffon, Borzoi, Canaan Dog, Chow-Chow,

Fox

Terrier, Siberian Husky, Jindo, Kangai, Pekingese, Rottweiler, Taigan,

Thai Ridgeback, Whippet, and several dogs from China). All sequences

were

derived from Salukis out of the Middle East or bred in Europe and

America.

These

results

show

that

the genetic background of the Saluki is one of

the most complex of all breeds in this study. Clearly, the Saluki

is not a distinct population derived from a single “Saluki-Eve”. Local

Middle Eastern breeds such as Akbash and Canaan Dog appear several

times

among the Saluki’s related breeds. Whether this is because of

incorporation

of Saluki-like dogs into these breeds or vice versa remains unclear.

The

Saluki shares sequences also with the Afghan, the Taigan, the Tazi and

the Borzoi. Since these sequences are also shared by other,

non-sighthound

breeds, it is difficult to understand the direction of breeding:

a sighthound female crossed with those other breeds or a female of

those

other breeds crossed with a sighthound male. If such crosses

happened,

they may have been several thousand years ago, as the timeline of these

events can not be resolved with this study. The Afghan and Taigan share

a sequence unique to both, suggesting some, possibly ancient,

relationship,

in addition to sequences shared with several other breeds.

This

study

indicates

that

the Saluki is a local Middle Eastern breed which

has been expanded genetically by incorporation of three minor and three

major maternal lines shared with few or with many other breeds. A

single sequence is shared with the Sloughi, but is also shared with 23

other breeds and a large group of indigenous dogs from China and

Indonesia.

Therefore, this single shared sequence does not prove an affinity of

maternal

lines specific to the Sloughi. This contrasts with the more profoundly

shared maternal lines of the modern-day Saluki with local Middle

Eastern

dogs such as Akbash and Canaan Dogs, but also other Eastern sighthounds.

Saluki

~

Sloughi

The

Saluki and Sloughi compared.

These

results

reveal

that

the Sloughi breed is not integrated in the Saluki’s

gene pool, therefore cannot be derived from the Middle Eastern Hounds

brought

by the Arabs when they invaded North Africa some 1300 years ago. If

this

happened,

it

was

of such a minor scale that it had virtually no impact

on the maternal lines of the Sloughis of this study. In fact, the

three distinct maternal lines of the Sloughi suggest that those

maternal

lines might have been geographically isolated in Africa for several

thousand

years. If combined with the shared sequence with the Basenji and other

African breeds, up to 67% of the female population of the Sloughi might

have been in North Africa for a very long time.

The

results

for

the

Saluki indicate that the breed derives up to 62.5%

from possibly local females, which, however, may be common to other

local

dogs such as Akbash and Canaan Dog. The number of sequences

shared

by Saluki and Akbash is larger than those shared with any of the

geographically

nearby sighthounds, including the Sloughi. These results do not

support

the idea that the Saluki of today has been “purebred” over the last

several

thousand years and thus might be the oldest purebred dog breed, except

if we assume that such integration happened long ago. The fact

that

non-sighthound breeds such as Akbash and Canaan dog share more maternal

lines with Salukis than Salukis share with other sighthounds does not

provide

support for the Saluqi hypothesis.

To

conclude,

these

results

support

the idea that the Sloughi and Saluki of

today are distinct breeds with genetic ties to each other that are no

more

profound than those of either to many other breeds.

We

hope

that

this

essay will provide for a more rational basis of future

discussions. We deliberately refrained from quoting sources for

the

various ideas in order to allow everyone the opportunity to reconsider

those ideas in the light of these genetic results. It needs to be

stressed, however, that these conclusions are based on a limited sample

size and might undergo some revision once more samples are

included.

Nevertheless, the genetic data presented here for the first time

support

the notion previously espoused by F. Amherst and others that these

sighthound

breeds are distinct. We propose that these breeds should remain as

separate

breeds until full resolution of their genetic background is completed.

A more complete resolution of all the questions raised here will have

to

wait until the paternal side is known through analysis of the male Y

chromosome.

Finally, correlating the genetic differences described here to

differences

in phenotype will only be possible after the dog genome * (footnote) is

completed and the relationship of various genes to phenotype have been

clarified, research that will require many more years.

Acknowledgments

We

thank

Dr.

P.

Savolainen

for improving an earlier version of this manuscript.

References:

Amherst

F.

1907.

Oriental

Greyhounds.

In Cassell's New Book of the Dog, ed. R

Leighton,

pp. Ch LVI. London: Cassell & Co

Savolainen

P,

Zhang

YP,

Luo

J, Lundeberg J, Leitner T. 2002. Genetic evidence for

an East Asian origin of domestic dogs. Science 298: 1610-3

Waters

H,

Waters

D.

1969.

The Saluki in History, Art and Sport. Newton Abbot:

David & Charles. 112 pp.

Footnote

mtDNA stretch

All

genetic

information

is

built of DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid), a giant

double helical molecule that consists of four distinct units, called

bases,

arranged in two parallel strands. These bases are A, T, C, G

(Adenine,

Thymine, Cytosine, Guanine) A interacts with T, C interacts with

G. These interactions form bridges that hold the double stranded

DNA together in a full mirror complement of each other. In essence, the

DNA is a biological digital storage system that has four signals (the

four

bases) to code for proteins.

The

genetic

information

(DNA)

of

all mammals is stored predominantly in the

nucleus of each cell. In addition, a small fraction of DNA is

also

found in mitochondria, the power plants of each cell. This

mitochondrial

DNA (mtDNA) is only inherited from the female to her offspring.

No

male mtDNA contributes to the next generation. Therefore each

male

is a dead end with respect to inheritance of mtDNA information.

Analyzing

the sequence of mtDNA provides thus exclusive information only about

the

mother’s side of a given dog. Only information about the mother,

grandmother, great grandmother etc of a dog will be revealed.

Since

mtDNA, like any other DNA, encodes information in the arrangement of

the

four bases, one can compare the arrangements of these four bases to

study

similarities of animals that result from common inheritance.

Thus,

sequencing a stretch or segment of the mtDNA will provide genetic

information

about the inherited relatedness of dogs. Such an analysis would

be

comparable to ordering all of the letters on this page into a single

line

without any interruptions and comparing this with files similarly

obtained

of pages from other books. Logically, only faithful copies of the

page would show a high resemblance in the sequence of letters over such

a long stretch.

Base

substitution.

Altering

the

information

encoded

in the orderly arrangement of bases on

the DNA requires altering the sequence of bases. Such an

alteration

is called a mutation. Such mutations can do a number of

things.

In many cases, mutations change a single base. Thus, instead of

an

A it will substitute that for a G, for example. Such base

alteration

rates typically range in the order of several hundreds or thousands of

years, depending on the sequence in question.

Dog

genome.

The

genome

is

all

the inherited information or DNA carried from one

generation

to the next in a given being. The genome of four mammals has thus

far been sequenced, humans, mice, rats and dogs. A comparison

revealed

that dogs and humans share approximately 90% of their genes.

ABOUT DR.

BERND FRITZSCH

ABOUT

DR.

DOMINIQUE

DE

CAPRONA

|